13 August 1999

Up close and political with Nurul Izzah, who has proved tougher than anyone expected

By Santha Oorjitham

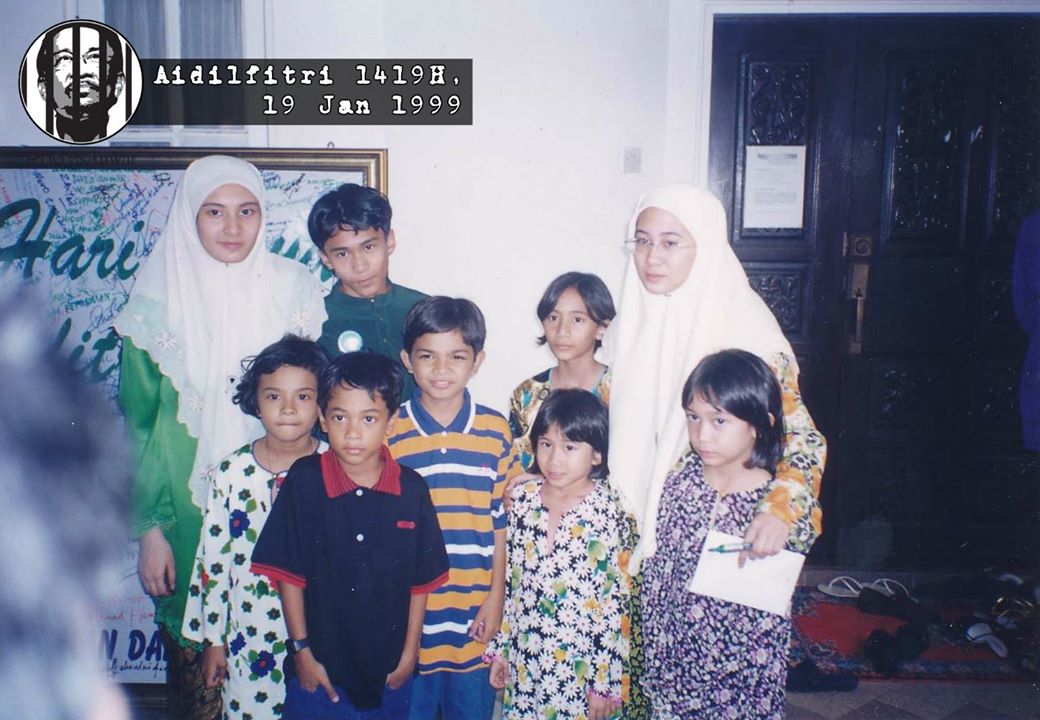

IT HAS BEEN QUITE a year for Nurul Izzah Anwar. In April of 1998 she left her family for the first time to attend college. Then, one semester into her degree, her father, Anwar Ibrahim, was fired as deputy prime minister and finance minister. Nurul Izzah rushed back to be with her family. Anwar was dragged from their home before her eyes and later charged with abuse of power and sexual misconduct. A lurid trial followed that was rife with homosexual allegations against her father. It ended with Anwar sentenced to six years in prison. At the time just 17, Nurul Izzah watched her mother, Dr. Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, take up Anwar’s political struggle and launch Keadilan, the National Justice Party, which will contest upcoming elections.

Before long, the shy teenager was herself traveling the globe and making impassioned, if unpolished, speeches. When she wasn’t doing that she was attending her father’s trial and looking after her five siblings. Nurul Izzah’s sudden plunge into the spotlight drew criticism from certain quarters that she was being used to prop up her father’s political support. Even close relatives expected her to crumble under the strain. And yet, much to her own surprise, she has endured – proving, perhaps, that Nurul Izzah is very much her father’s daughter.

Nurul Izzah was born into politics. When her father and mother were courting, Anwar was still considered a radical and hence an arrest worry. Wan Azizah’s father, Wan Ismail Wan Mahmood, suggested that the couple wait until the political climate improved. They went ahead and married in February of 1980. Ten months later, on Nov. 19, Nurul Izzah (Light of Success) arrived. Early on, her mother recalls, the little girl demonstrated an ability to ride out emotional and physical pain. When she was about three years old, Nurul Izzah fell and hit her head. The cut required two stitches, without anesthetic. “She cried a little,” says her mother, “but she was pretty tough.”

Wan Azizah did not have her second child until Nurul Izzah was four, so she spent a lot of time with her first born and they developed an extraordinarily close relationship, even for a mother and daughter. Eventually, the house was filled with the chatter and play of six children, five girls and a boy. From the beginning, Nurul Izzah played the capable big sister to the rest.

Wan Mahmood recalls a “very active little girl, very cheerful, very bright.” They would sing English and Malay songs together, with Nurul Izzah holding a cup like a microphone. While many people say the girl later became shy, her grandfather, who ran the government’s Psychological Warfare Unit for some 30 years, says from the beginning he saw “her quality, her personality, which is extroverted, not shy. She could get along with anybody, young or old.” It was after Nurul Izzah started school, recalls her uncle Rusli Ibrahim, Anwar’s younger brother, that she became more withdrawn and focused on her studies. “Her heart was in her education because she’s the eldest,” he says. “With five under her, she had to show the best to her younger brothers and sisters.”

During her early childhood, Nurul Izzah did not see much of her father; his political career was just taking off and he was always busy. Things changed, however, when she was 12; Anwar had been named deputy prime minister and, she recalls, he decided to make more time for his family. When her father went overseas with her mother, she says, he called his children every day. “We always tried to have family dinner three or four times a week,” says Nurul Izzah. “Most days, he’d come home for lunch and we’d discuss.” Politics, however, rarely intruded, and Nurul Izzah says she made it personal policy not to ask her father about his job. Until, that is, her friends at school began complaining to her about the controversial Bakun Dam project in Sarawak. Then she asked her father “why it was still on when all the nature foundations were condemning it. He would say: ‘What can I do?'”

During those days, the family lived in the seven-bedroom deputy prime minister’s official residence in Kuala Lumpur’s tony Damansara district. In truth, Nurul Izzah never liked the place. It was old. There were termites. The plumbing was cantankerous. And the grounds were almost surrounded by jungle. It was creepy at night. “We were used to our own house, and this was so grand,” Nurul Izzah recalls. “It was not ours; it was government property. My father would scold us if we didn’t turn out the lights and would tell us not to waste electricity.” Farang, one of Nurul Izzah’s friends, slept over and recalls they wouldn’t move around in the house at night but would lock the bedroom door and listen to CDs.

Nurul Izzah’s room was crammed with books. Among her favorite writers were Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters and the World War I British poet Wilfred Owen, of whom she had posters. Owen seems a strange choice for a contemporary girl, but Nurul Izzah says his verse struck a chord. “When I read it, I saw the value of life, how war destroys everything. The notion of death and how you should treasure life.” Although she was in the science stream at the Assunta Secondary girls school, Nurul Izzah wanted to do English Literature as an A-level subject, so she took outside tuition. “We would argue about literary terms,” says her former teacher, Veronica Loo. “She’s very artsy and has a literary streak which she inherited from her father.”

At home, Nurul Izzah played the piano but later took up the guitar – inspired by her favorite band Radiohead, a British alternative act. She especially likes the song “Paranoid Android,” which goes like this: When I am king you will be first against the wall/With your opinions which are of no consequence at all/Ambition makes you look very ugly/Why don’t you remember my name/Off with his head.

An A student, Nurul Izzah was a prefect throughout school. At first she was reluctant to take the post. “She wanted to keep a low profile,” Loo recalls. “She was afraid [the prefectship] was [offered] because of who she was.” By all accounts, Nurul Izzah made a good prefect – “stern,” says her pal Farang, “but not too strict.” But Nurul Izzah didn’t like the job. “It reminded me so much of the police,” she says. “I had to give out detention slips.” Her friends recall a quiet student who wanted to be treated like everyone else and shied away from being photographed. Nonetheless, Nurul Izzah revealed a talent for the stage and was active in the English Literary and Debating Society, which put on regular concerts. In 1996, she played the Lady of Shalott in a dramatization of the Alfred Lord Tennyson poem. Her parents were in the audience. “I ‘died’ in front of them,” she says. “I loved it!”

That was before Nurul Izzah began wearing a tudung, the headscarf favored by traditional Muslim women. She insists there was no pressure from her father, that it was her decision. “I was growing up. Everyone wants to look beautiful, but it’s a form of decency and modesty.” By then, Nurul Izzah had finished her O levels and was preparing to start university. In the interim she studied the guitar, French and the Koran. “My father didn’t want me to waste my time,” she says. When she wasn’t busy studying, Nurul Izzah and her friend Farang went to movies and slept over at each other’s homes. “But I didn’t meet boys,” she says. “My parents were quite strict.”

Nurul Izzah decided on a bachelor of science in chemical engineering. “I wanted to go to Cambridge, but my father wanted me to go to a local university because he was promoting local studies. I understand what he was saying now. I can always do my masters overseas.” Farang recalls “there were lots of tears” when Nurul Izzah headed north to Petronas University of Technology in small-town Tronoh, Perak. Farang and Wan Azizah went up to Tronoh to settle Nurul Izzah in. They hung up her Radiohead posters and pertinent sentences from the Koran. “It was my first time living away from home,” says Nurul Izzah. “My father called me every day.” On Aug. 9, the day before Anwar’s 51st birthday, she wrote to him. “I said: We’re so lucky our task in life is only to study, get good grades and get a degree. I don’t have to fight for a cause. I’m reminded of your time [as a student radical] and I wonder how you did all that. It was amazing. I wish I had something to fight for.”

IN LATE AUGUST, her father’s calls became more sporadic. Rumors were circulating on campus that he was in trouble. But Nurul Izzah, the good student, had no time to read the newspapers and, besides, she was busy studying for her exams. On Sept. 2, 1998, Nurul Izzah was preparing for the mathematics final, to be held the following day. On her way home from college, she caught sad looks from fellow students, but no one said anything. She wondered: Why are they looking at me like that? At about 7:30 p.m., her best friend called and said: “I’m so sorry.” Nurul Izzah asked why. “Haven’t you heard?” the friend replied. “The PM has sacked your father.” Nurul Izzah broke down in tears. Finally, at midnight, she managed to get her father on the phone. “He said: ‘Izzah, be brave. I will fight on. Take your exam and don’t worry about me.'” The next day at school, no one seemed to know what to say. “I think they were scared,” Nurul Izzah says. “I didn’t really get to know everyone because I was new there.” But she recalls close friends rallying around her.

Nurul Izzah wrote her math exam and returned to Kuala Lumpur. By then the electricity and the water to the official residence had been cut off. The family moved back to their home in Damansara Heights. For the next three weeks, crowds poured into the house, churning the garden into a sea of mud. Outside, vendors set up stalls selling food, drinks, tapes of Anwar’s speeches and bumper stickers calling for “Reformasi.” Then, on Sept. 20, balaclava-clad members of the Special Action Forces smashed their way into the house, as police helicopters swept the grounds with blinding searchlights. The authorities bundled into a van Anwar, his wife, Nurul Izzah and the rest of the family – except for one daughter who was left behind in the chaos. Later, her father was transferred to a police car and taken to prison. He was charged with five counts of corruption and five of sexual misconduct. Nurul Izzah’s life had changed forever.

Over the next few months she would watch her father fight for his political life. She would endure the seedy allegations of his alleged affairs with his private secretary’s wife. She would listen to even more sordid testimony about her father’s alleged homosexual dalliances with her mother’s former driver Azizan Abu Bakar, and Anwar’s adopted brother, Sukma Darmawan Saasmitaat Madja, a man Nurul Izzah has known since childhood. She watched as the police dragged into court the mattress her father allegedly used for his trysts. For her, the 77-day trial was a “test of patience.” Now, she is attending Anwar’s trial on charges of sodomy (illegal in Malaysia), which she characterizes as “tougher.” Never does a day go by when she is not worrying about “the verdict, about my father.” She looks sadder in court these days.

In the aftermath of Anwar’s sacking, arrest and conviction, many of Nurul Izzah’s friends abandoned her, says Rozela Mohamad Dahlan, 19, a former schoolmate who lives near the family. “That shouldn’t happen to her,” says Rozela. “Maybe they were afraid and their parents didn’t allow them to see her.” Farang says: “That was the sad part. It really disturbed her. Now, she’s seeing who are her true friends.” But Nurul Izzah is empathetic. “My friends were quite supportive, but they’re scared. They are well-to-do and busy getting their degrees.”

Either way, the sleepovers and movies with Farang and Rozela are over. Nurul Izzah is all politics these days. Rozela professes amazement at her friend’s sudden transformation. She recently accompanied Nurul Izzah to a political event, where she wore a sash that read: “Puteri Reformasi” – or Princess of Reformation. “She talked about reformasi, the struggle,” says Rozela. “I was quite surprised; she’s changed a lot.” Nurul Izzah, adds Rozela, is still the same person on the phone – “very talkative. But her thinking is getting more mature. If I make stupid jokes, she advises me like a sister.”

Nurul Izzah is a poignant symbol for both her father and the reformasi cause, partly because many of the people who support Anwar are young like she is. Nurul Izzah has yet to address a hostile crowd – and given her age and experience most people are going to give her a break. In speeches, she tends to focus on her father’s situation and the need for young Malaysians to be more forthcoming about their views. When audience members ask questions about politics, one of her mother’s aides sometimes assists. And she has received more than one nasty e-mail to her father’s website. At other times she has played to sympathetic ears, including those of Presidents B. J. Habibie of Indonesia and Joseph Ejercito Estrada of the Philippines. In Manila, Nurul Izzah also met Kris Aquino, TV host and daughter of ex-president Corazon Aquino. The two young women had much to talk about, specifically what it is like to be thrust into the political limelight when your mother takes up the father’s mantle.

There are those who consider Nurul Izzah’s teenage politicking unseemly, not to mention the fact that a young Muslim woman is hobnobbing with elderly gentlemen, however eminent. “She has been made use of by certain parties to give speeches, to condemn the Malaysian government and Dr. Mahathir Mohamad,” says Ibrahim Ali, deputy minister in the PM’s department. “When a daughter speaks of her father, she will say he is correct. It takes a third party, rather than the wife or daughter, not to be emotional.” Nurul Izzah denies she is being manipulated for political purposes. “I have to clear [my father’s] name and the family honor. How can I just sit there and do nothing?”

Nonetheless, there is much speculation that Nurul Izzah will follow Anwar and one day run for public office. She was supposed to return to university in June, but has taken another six months off. Anwar’s lawyers and her mother’s doctor friends are urging Nurul Izzah to ditch chemical engineering for political science; she is resisting the notion. When she was on a speaking engagement in Wales recently, Malaysian students asked her if she wanted to become a politician. “I’ll cross that bridge when I come to it,” she says. And she has become notably more concerned with her public appearance. In the past, even when she started wearing the tudung, Nurul Izzah favored casual attire. These days, when she goes out, she is wearing the baju kurung, the traditional Malay tunic and long skirt.

Typically, Nurul Izzah leaves the house before nine a.m., accompanied by one or more of her sisters. Traffic willing they spend half-an-hour with their father at the court lockup before he heads to court. If the session is open to the public – sometimes the judge holds an in-camera session – Nurul Izzah watches the defense and prosecution tussle over procedure and legal technicalities. Later, Anwar’s daughter attends to her political obligations. Usually she speaks to students, but more recently she has been heading into the kampungs to address ordinary people.

At the family home on Jalan Setiamurni 1, much has returned to normal – and much hasn’t. The grass has grown back, but the broken panels in the front door and window are boarded up – a deliberate reminder, perhaps, of the state’s heavy-handedness. The dining room has become a meeting room, and the corridor leading to the library (now an office) has been blocked off with a sign that reads: “Only workers allowed entry.” Today, Nurul Izzah shares a room with her mother. Her four sisters also share a bedroom. They are too scared to sleep alone. To her younger siblings, Nurul Izzah is no politician, no Princess of Reform. She is still the big sister that she has always been.

Extracted from Asiaweek.com

http://www-cgi.cnn.com/ASIANOW/asiaweek/99/0813/sr1.html